My previous post on the Evangelical divide was based on a text written by Arminian theologian Roger Olson.

In case some people doubt such a divide really exists, I add here part of an article on this topic published in First Things by the Reformed theologian Gerald McDermott, the Jordan-Trexler Professor of Religion at Roanoke College and Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Baylor Institute for Studies of Religion, editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evangelical Theology and coauthor of The Theology of Jonathan Edwards (Oxford).

I add here, as a teaser, the first part of this longer text (bold emphases are mine).

* * *

Long confused with fundamentalism by most of the academy and dismissed as intellectually inadequate, evangelical theology has in the last two decades become one of the liveliest and most creative forms of Protestant theology in America. Not long ago the Lutheran theologian Carl Braaten noted that “the initiative in the writing of dogmatics has been seized by evangelical theologians in America. . . . Most mainline Protestant and progressive Catholic theology has landed in the graveyard of dogmatics, which is that mode of thinking George Lindbeck calls ‘experiential expressivism.’ Individuals and groups vent their own religious experience and call it theology.”

Evangelicals generally believe theology is reflection on what comes from outside their experience as the Word of God. For that reason—that they talk not primarily about themselves but about a transcendent God whose self-revelation must be wrestled with—they not only have more to say than mainline Protestantism, but more interesting things to say.

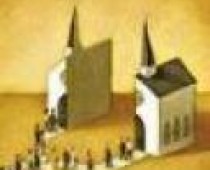

Most evangelicals believe that they are bound by the Word of God understood as a transcendent, authoritative revelation. But not all are so convinced, and therein lies a problem for the future of evangelical theology and the future of evangelicalism. The rising generation of evangelicals is not as socially or theologically liberal as has been thought (See Byron Johnson, “The Good News About Evangelicalism,” FT, February), but their theological leaders are splitting in ways that threaten the future integrity of their movement and the source of its theological creativity.

Evangelical theology has long been divided between those who emphasize human freedom to choose salvation (Arminians) and those who stress God’s sovereignty in the history of salvation (the Reformed). Now this old division has been overshadowed by a larger division between new opposing camps we may call the Meliorists and the Traditionists. The former think we must improve and sometimes change substantially the tradition of historic orthodoxy. The latter think that while we might sometimes need to adjust our approaches to the tradition, generally we ought to learn from it rather than change it. Most of the Meliorists are Arminian, and most of the Traditionists are Reformed, though there are exceptions on both sides.

This new division has developed from challenges by some of those who call themselves “post-conservatives.” Led by Meliorist theologians like Roger Olson and the late Stanley Grenz, they argue that “conservative” theology is stuck in Enlightenment foundationalism, which seeks certainty through self-evident truths and sensory experience, sees the Bible as a collection of propositions that can be arranged into a rational system, believes doctrine to be the essence of Christianity, and, because it does not realize the historical situatedness of the Bible, constructs a rigid orthodoxy on a foundation of culture-bound beliefs. Responding in part to evangelical excesses in the inerrancy debates of the 1970s, post-conservative theologians developed an understandable distaste for rationalistic, ahistorical, and un-literary readings of Scripture.

* * *

If you are interested, you may read HERE the entire article, titled “Evangelicals Divided. The battle between Meliorists and Traditionists to Define Evangelicalism”. I would suggest to you to also read some of the comments, where the author interacts (not very satisfactory, in my estimation) with some of the authors he criticises in this paper.

Comment: Although I refuse to be constrained to choose between the Reformed and the Arminian theological ideologies, it may not come as a surprise for those who are reading this blog, at least from time to time, that I have little patience for the self-serving triumphalism of McDermott’s mostly (neo)Reformed analysis of the current situation in Evangelicalism and that I have a lot of sympathy for the post-conservative critique of the neo-fundamentalist position find in bold in the last quoted paragraph and espoused here by McDermott (be it in a softer form than that of John Piper or Al Mohler).

This being said, I let you enjoy further reading. And comment, if you feel so inclined.

Your English is impeccable, Dănuţ. But McDermott’s article and subsequent conversation are about the role of Scripture and the Great Tradition especially in the Meliorists’ [evangelical] theologies. I see no self-serving triumphalism in this, but a genuine (and at times humble) concern to re-articulate at least part of the Great Tradition (i.e., penal substitution) in the face of its recent detractors. McDermott and McClymond are certainly more gracious (and more open) than Olson in their take on evangelicalism. Anyway, I kind of appreciate that you draw attention to both articles on your blog.

LikeLike

How could he ‘stab at the other side’ when the post-conservatives are the ones criticising the present state of Evangelicalism and the neo-reformed feel very well in their skin, thinking they are the only ones who are fully and faithfully following Christ? It does not make sense. Or it is just my poor English (or my poor intelligence) staying in the way of a correct understanding.

LikeLike

Your bold print is McDermott’s stab at the other side. He is ironical.

LikeLike

Look at the sentences I have underlined in the first two phrases. I have rarely read a more triumphalistic and unreal evaluation of Evangelical theology in America, which anybody can see is in a deep crisis, as is the whole movement. This sounds to me like poor apologetics rooted in complacency.

LikeLike

Dănuţ, what exactly do you find “self-serving triumphalism” in Gerald McDermott’s analysis (and/or subsequent conversation)?

LikeLike